Histology to EM

Histology to EM

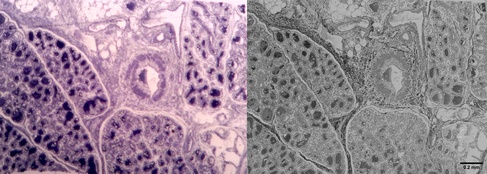

Lactating mammary gland - methylene blue staining of a semi-thick section (left) and corresponding EM image of an adjacent thinsection in SEM blockface imaging (right) – tissue derived from FFPE material (FFPE block kindly donated by the team of the Cambridge PDN Histology Teaching Room, EM by CAIC).

In the clinical setting, biological material is routinely investigated using histological staining methods followed by examination by light and sometimes fluorescence microscopy. In some cases, tissue structures are found, which point towards a certain diagnosis, but the histology resolution is too low to provide certainty. Electron microscopy to image these structures at higher resolution is then sometimes envisaged retrospectively.

If intended initially for histology only, tissues are usually not fixed optimally for EM studies, and the material available is either preserved in formalin or as a FFPE block (formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded). Formalin-fixed material can give very good results in EM, especially if the time lag between tissue excision and fixation was kept very short. In contrast, expectations as to EM image quality have to be moderated when working from FFPE blocks. These tissues have already seen extensive processing, including solvent dehydration and infiltration with paraffin and have to undergo similar procedures a second time to become an EM resin block. The solvent dehydrations in particular can extract tissue lipids and membrane structures, resulting generally in much poorer tissue morphology compared to tissues processed optimally for EM from the start.

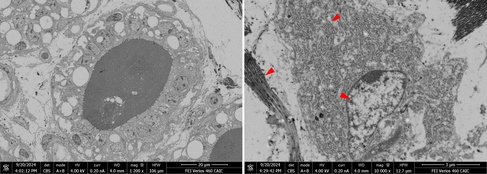

SEM blockface image of an alveoli of a lactating mammary gland (left) and detail of a likely secretory cell in the surrounding tissue away from the alveolus (right). Due to working from FFPE material, most cytoplasmic membranes have been removed, but due to the decoration with protein-rich ribosomes, the structure of the rER is still recognizable. Other well-preserved structures are usually the nuclei and collagen bundles/fibrils of the extracellular matrix (red arrowheads).

Nevertheless, there are cases were EM imaging of formalin-fixed material or FFPE blocks can be helpful, especially when imaging protein-rich or stable structures which preserve well with aldehyde fixation and are not extracted too easily.

Adult-onset neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis in a smooth-haired dachshund

(Case Report by Diogo Gouveia, Max Foreman and Emilie Cloup, Dick White Referrals, doi:10.1002/vrc2.991)

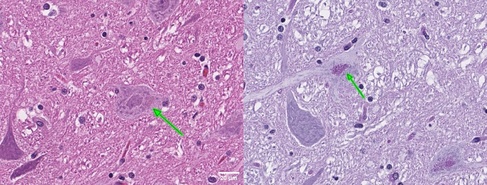

An adult, smooth-haired dachshund had to be euthanized after presenting with neurological symptoms of increasing severity and not responding to various treatment regimes. Symptoms and treatment history were suggestive of a degenerative/lysosomal storage disease and post-mortem histology indeed found intracytoplasmic, granular material particularly in neurons of the hypothalamus and thalamus.

Haematoxylin/Eosin (left) and periodic acid-Schiff stains revealing intracytoplasmic, PAS-positive brown granular deposits (green arrows) in neurons of the thalamus (Dick White Referrals).

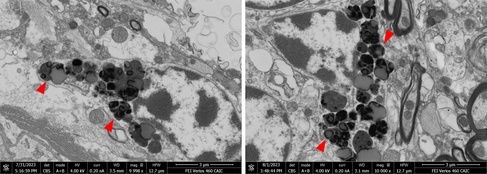

Formalin-fixed tissue was subsequently submitted to CAIC for EM analysis. SEM blockface imaging was able to quickly localize granular deposits even in large tissue sections. Electron-dense lipofuscin granules of varying sizes were found along with lipid droplets and electron-lucent material. The electron microscopic findings supported a diagnosis of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (NCL).

Electron-dense lipofuscin granules in dog brain imaged by SEM blockface imaging (CAIC).

Genetic testing did not identify the causative genetic mutations usually associated with early-onset NCL in this dog breed. This case could therefore present a novel subtype of NCL, due to so far unidentified genetic mutation(s), leading to the onset of clinical symptoms only in adult life.